Wine merchants liable for copyright infringement and passing-off over label artwork

The High Court has found that a UK wine importer and distributor infringed the copyright in a drawing by British visual artist Shantell Martin MBE, which had been reproduced without permission on the labels of imported wine bottles.[1]

David Stone, sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge, considered that the wine merchant was also liable to Ms Martin for passing the labels off as endorsed by her. Although two later label designs avoided liability, the case illustrates the legal risks faced by customers that rely on overseas suppliers to manage intellectual property rights.

Background

The first claimant was Shantell Martin, a British-born visual artist based in New York and internationally recognised for her distinctive monochromatic line drawings. The second claimant was Found the Found LLC (FTF), a company incorporated in New York, to which Ms Martin assigned copyright in the relevant artwork in June 2021.

The defendants were: Bodegas San Huberto SA (BSH), an Argentinian wine producer; GM Drinks Ltd (GMD), the exclusive UK importer and distributor of BSH products; and GMD’s director, Marc Patch.

The work in question was a wall drawing created by Ms Martin in 2017 for a solo exhibition at the SKG Museum in Buffalo, New York (as shown below).

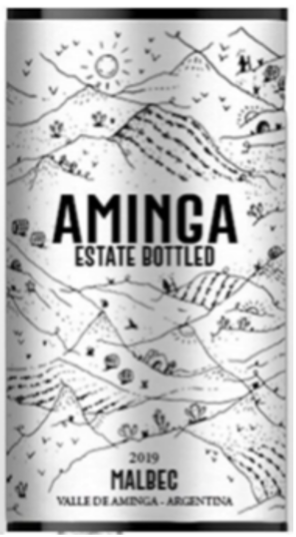

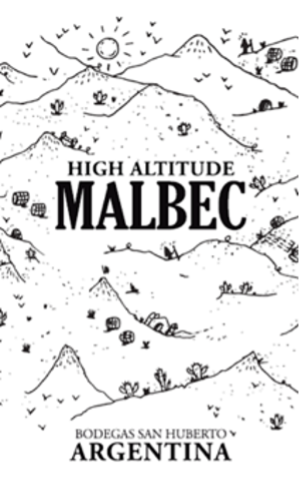

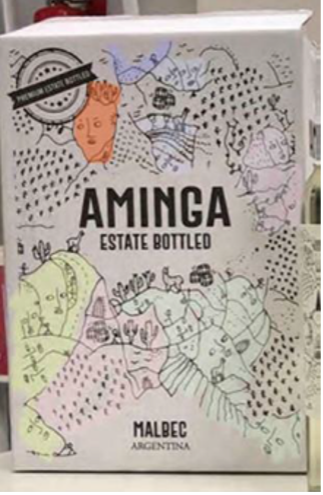

The wine labels were as shown below.

At some point after January 2020, GMD imported wine bearing the first label into the UK. Following a complaint by Ms Martin to GMD in April 2020, BSH arranged for the first label to be redesigned, which resulted in the second label. In October 2020 Ms Martin’s lawyers sent a letter complaining about the second label, and then BSH arranged for the design of the third label. Ms Martin’s lawyers complained about that as well, and a fourth label was designed, which was not mentioned in the trial.

As the owner of the copyright in the original work, FTF claimed primary infringement of copyright in the work under section 18 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA), i.e. by issuing copies to the public, as well as secondary infringement under sections 22, 23(a) and 23(b) of the CDPA, i.e. by knowingly (or with reason to believe) importing and dealing with infringing copies. Ms Martin also asserted that her moral right to be identified as the author was infringed under section 77 of the CDPA, and claimed passing-off on the basis of false endorsement in relation to the wine products bearing the first, second and third labels.

BSH did not attend the trial. Mr Patch represented himself and, with the court’s permission, GMD.

Copyright infringement

Subsistence and ownership

The judge noted that the CDPA confers protection where the author is either a British citizen or domiciled in a Berne Convention country at the time of creation. Ms Martin, a British national residing in the USA at the relevant time, satisfied both routes to qualification.

The judge began by affirming the subsistence of copyright in the underlying work under section 1(1)(a) of the CDPA, which protects “original artistic works”, including “graphic works” in accordance with section 4(1)(a). He accepted that Ms Martin’s wall drawing constituted an artistic work within this category, noting its distinctive visual style and originality.

Ownership of the work was addressed under a written agreement dated 2 June 2021, under which Ms Martin assigned the entire copyright to FTF, as well as all causes of action worldwide.

Infringement

The judge then considered the following questions:

- Was the first label a copy of the work, or of a substantial part of the work?

- If yes, had the second and/or third label been copied from the first label, such that they (or either of them) constituted a substantial copy of the work?

The judge applied the test for substantial copying, informed by the CJEU’s decision in Infopaq,[2] which held that even short extracts may be protected if they express the author’s own intellectual creation. In a UK context, this principle was affirmed in Pasternak v Prescott.[3]

Applying those principles, the judge held that the first label was “very clearly a substantial reproduction” of the work, and although the copy had been modified in some respects, the judge highlighted key elements from the work that had been identically reproduced in the first label (as actually used on the side of the case).

The judge did not, however, consider that the second and third labels were substantial reproductions of the work: while the second label had similarities to the work, those were “banal aspects of the language of drawing” and so not the expression of Ms Martin’s creativity, and the third label was further removed from the work than the second label. So, by contrast with the first label, the second and third labels were found not to have infringed FTF’s copyright.

Accordingly, the judge ruled that:

- GMD was liable for copyright infringement in relation to the first label: (i) under section 18 of the CDPA in relation to all the first-label products; and (ii) under sections 22, 23(a) and 23(b) only in relation to any first-label products dealt with from shortly after 13 April 2020, the date when Ms Martin had informed GMD of her rights in the work.

- GMD was not liable for copyright infringement in relation to the second label or third label.

- BSH and Mr Patch were not primarily liable for copyright infringement in relation to any of the first, second or third labels. Although Mr Patch considered BSH to be responsible for the copying that occurred, sections 18, 22, 23(a) and 23(b) set out strict-liability torts: intention or knowledge is not a precondition to liability.

Infringement of moral rights

The judge declined to determine the issue of infringement of moral rights because the claim was not included in the case’s list of issues. Yet he provided brief findings: the work was signed by Ms Martin, and while that would have been difficult to see on the copy of the work forwarded by Ms Martin by email to Mr Patch on 13 April 2020, it was open to Mr Patch to enlarge the image to view Ms Martin’s signature. As the first-label products were distributed to the public in the UK by GMD without an acknowledgement of Ms Martin’s authorship, the judge held that she would have succeeded under section 77 of the CDPA had she been permitted to run the point.

Passing-off

The passing-off claim was brought by Ms Martin in her personal capacity, as the owner of goodwill in her work. She brought the claim on two bases: classic passing-off on the basis of false endorsement, and also the inherent deceptiveness of the bottles, which she claimed conferred strict liability on BSH and GMD.

The judge applied the classic three-limb test set out in Reckitt & Colman,[4] which provides that a claimant must prove: (a) goodwill in the UK; (b) misrepresentation by the defendant leading (or likely to lead) the public to believe that the goods are associated with the claimant; and (c) damage to that goodwill as a result.

- Goodwill – Taking into account Ms Martin’s evidence of activities that she had undertaken in the UK, including a show at the Tate Modern, endorsements from brands such as Puma and The North Face, and her large social media following, the judge had “no doubt” that Ms Martin had the requisite goodwill in the UK (at all relevant times) to found an action for passing-off. He elaborated on where that goodwill lay, accepting that Ms Martin’s distinctive black-and-white line drawings rendered her work “instantly recognisable”.

- Misrepresentation – Ms Martin provided evidence of two instances in which UK-based customers were misled to believe that she had endorsed the product bearing the first label. Ms Martin noted that there were other instances that she did not record, but in any event the evidence presented to the court was sufficient to confirm misrepresentation. By contrast, the judge found there to be no misrepresentation in relation to the second and third labels, as they were not “sufficiently similar” to the work. He considered that no “not insignificant section” of Ms Martin’s market would consider that she was involved in the second-label or third-label products.

- Damage – The judge considered that damage would necessarily follow from the first-label misrepresentation, commenting that Ms Martin had suffered “damage to her existing licensing/endorsement business and to the distinctiveness of her signature style”.

As knowledge of passing-off is not an element of the tort, the judge found GMD liable for passing-off in relation to the first label, even without knowing that it was doing so. The judge found no liability for BSH, however, on the basis that there was no evidence that BSH did anything in the UK, despite Ms Martin’s case that the products were inherently misrepresentative.

Joint tortfeasorship

The final issue was whether the defendants (or any combination of them) were joint tortfeasors. The judge referred to the recent decision in Lifestyle Equities CV v Ahmed,[5] where the Supreme Court held that defendants will only be held jointly liable if it can be established that they had actual or constructive knowledge of the essential facts that made the act of the primary wrongdoer tortious.

The judge held that Mr Patch and BSH were jointly liable for secondary copyright infringement under section 18, 22, 23(a) and 23(b), but only in relation to the small number of first-label products that were sold after they were notified that the first label was an infringing copy.

The judge found no joint liability for passing-off. Before Ms Martin’s complaint of infringement, there was no evidence that either BSH or Mr Patch were aware of Ms Martin’s work. After notification of her rights, the judge was not convinced that either BSH or Mr Patch was aware of Ms Martin’s goodwill in the UK, and goodwill was not mentioned until most, if not all, of the first-label products were sold.

Conclusions

Overall, the judge ruled that:

- GMD was liable to FTF under section 18 of the CDPA for infringement of copyright in the work by issuing copies of the work to the public in the form of the first-label products, but might not be liable for damages before or shortly after 13 April 2020 if that infringement was innocent.

- GMD was liable to Ms Martin for passing the first-label products off as endorsed by Ms Martin.

- BSH and Mr Patch were joint tortfeasors only in relation to secondary copyright infringement, and solely in relation to the first-label products from shortly after 13 April 2020.

- No liability attached to any of the defendants in relation to the second or third label.

As the hearing was about liability, the judge did not provide a ruling on remedies, but provided some preliminary indications and invited the parties to attempt to settle the matter in light of his findings, failing which he proposed transferring the quantum proceedings to the Small Claims Track of the IPEC, with costs to be decided on the basis of written submissions.

Comment

The case serves as a useful reminder to any downstream entity in a supply chain of its potential exposure to claims for copyright infringement and passing-off, even where it may be unaware of the underlying infringement of intellectual property rights, and sends a clear message that customers should not rely solely on suppliers for IP due diligence. In particular, even if customers should seek suitable warranty and indemnity protection in their supply contracts, they should bear in mind that assurances from foreign suppliers cannot insulate domestic customers from liability to relevant third-party rights-holders, and so customers should consider investigating any material IP themselves.

The finding of personal liability in the case of Mr Patch also demonstrates the courts’ willingness to take directors’ own duties into account, particularly within small and medium-sized enterprises where direct oversight is more common. Further, the IPEC’s reluctance to consider points beyond the list of issues highlights the importance of adequate preparation for case management conferences, and of ensuring that a list of issues is sufficiently comprehensive.

Article written for Entertainment Law Review.